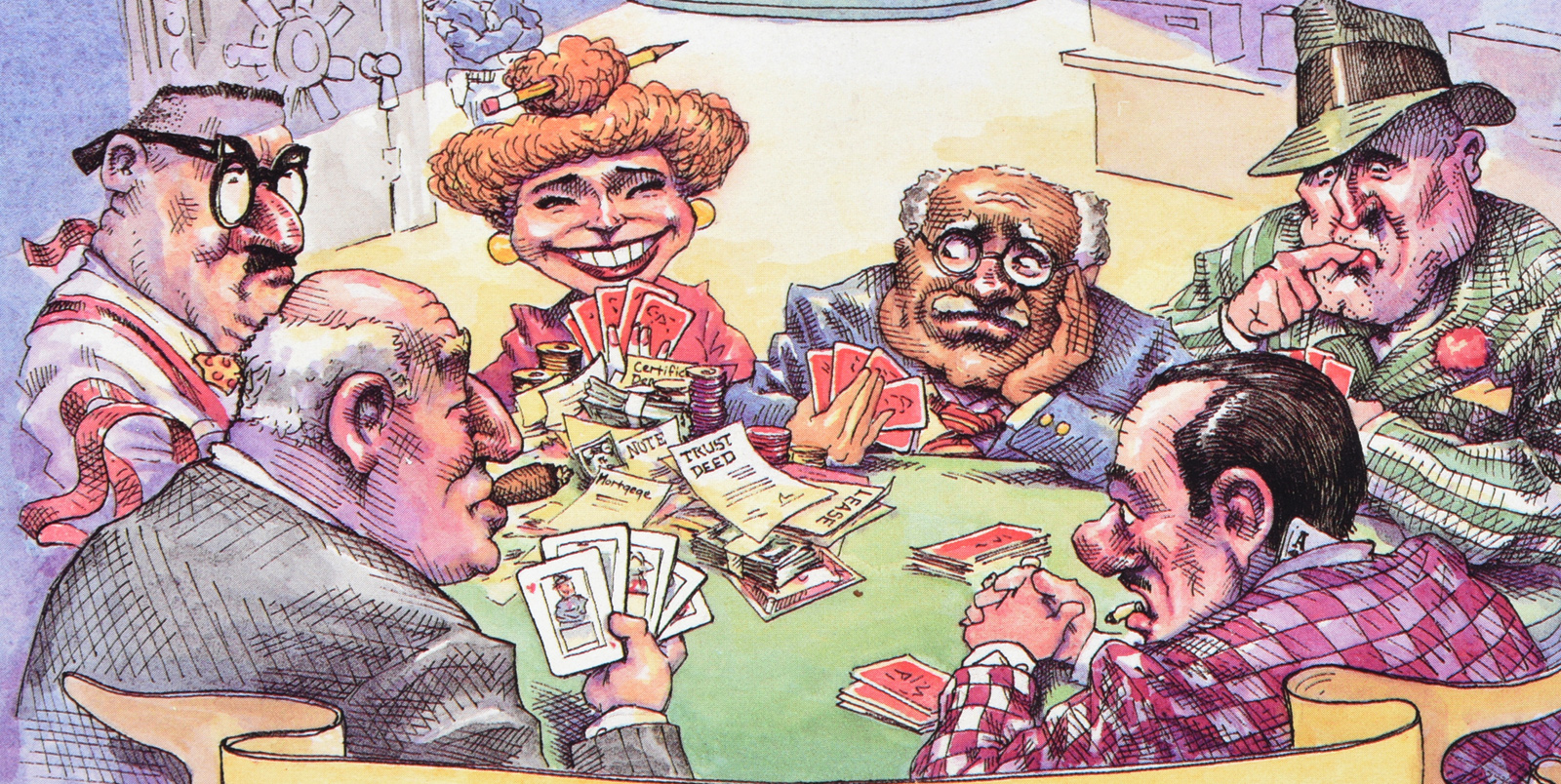

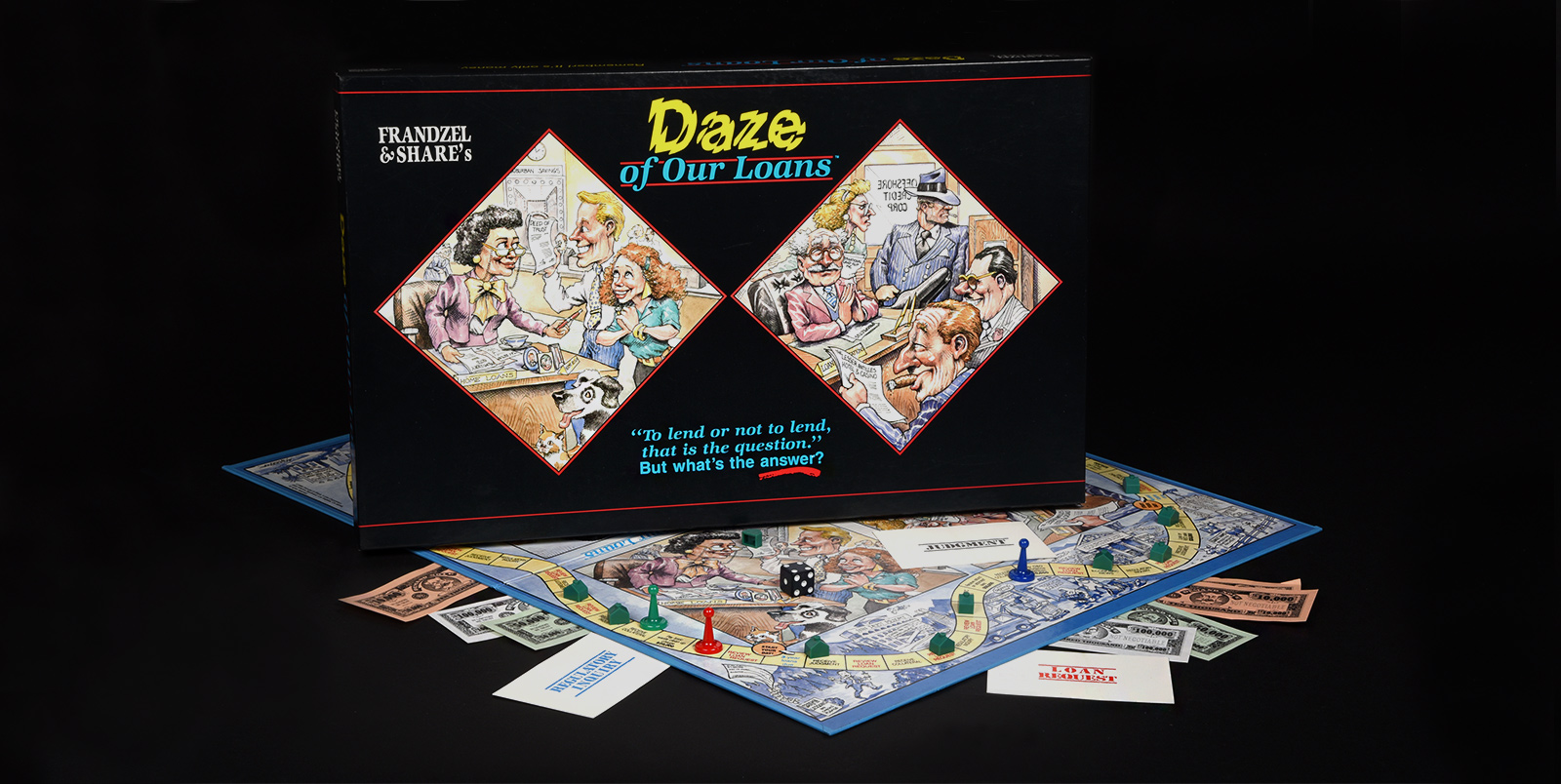

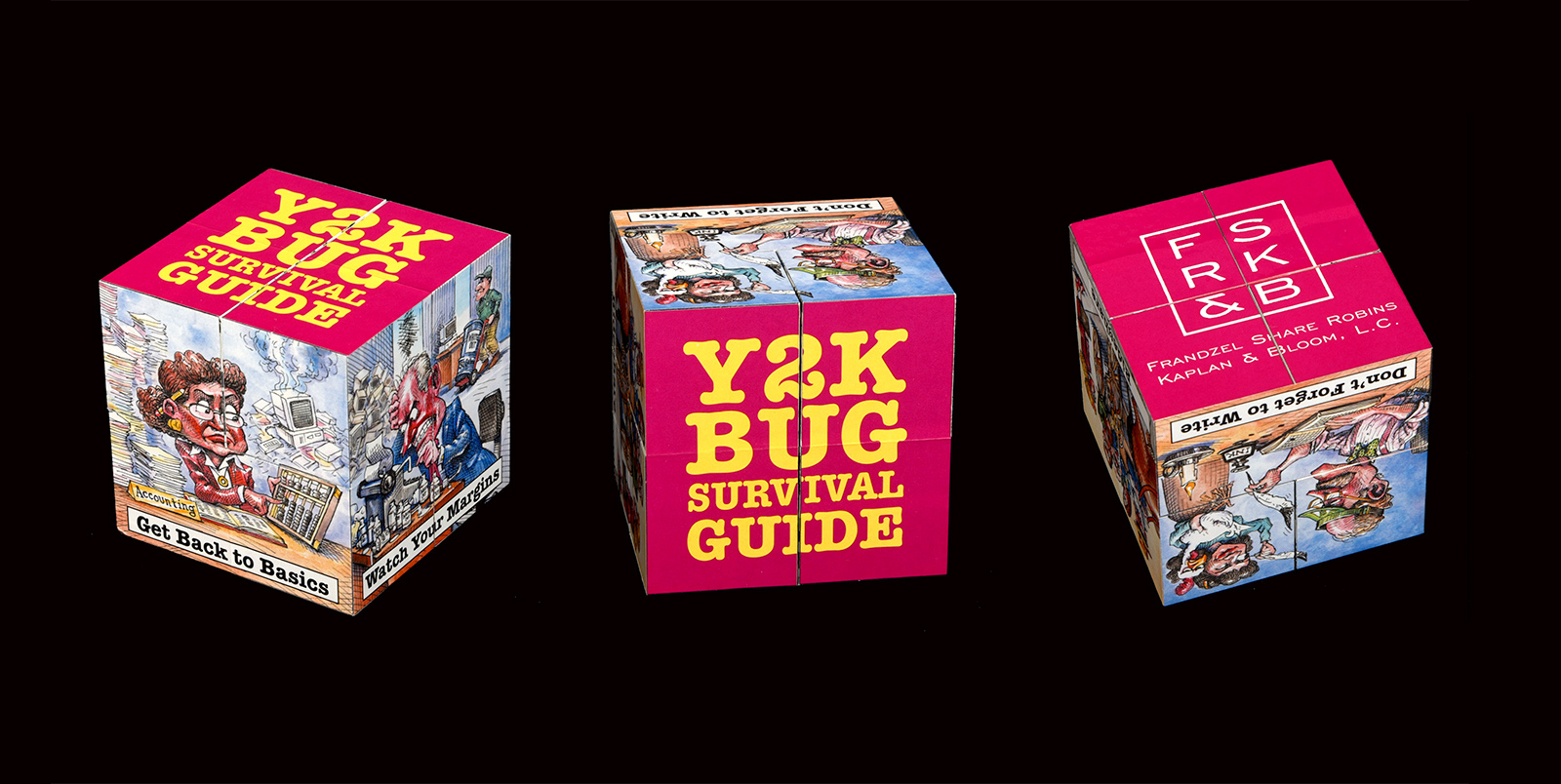

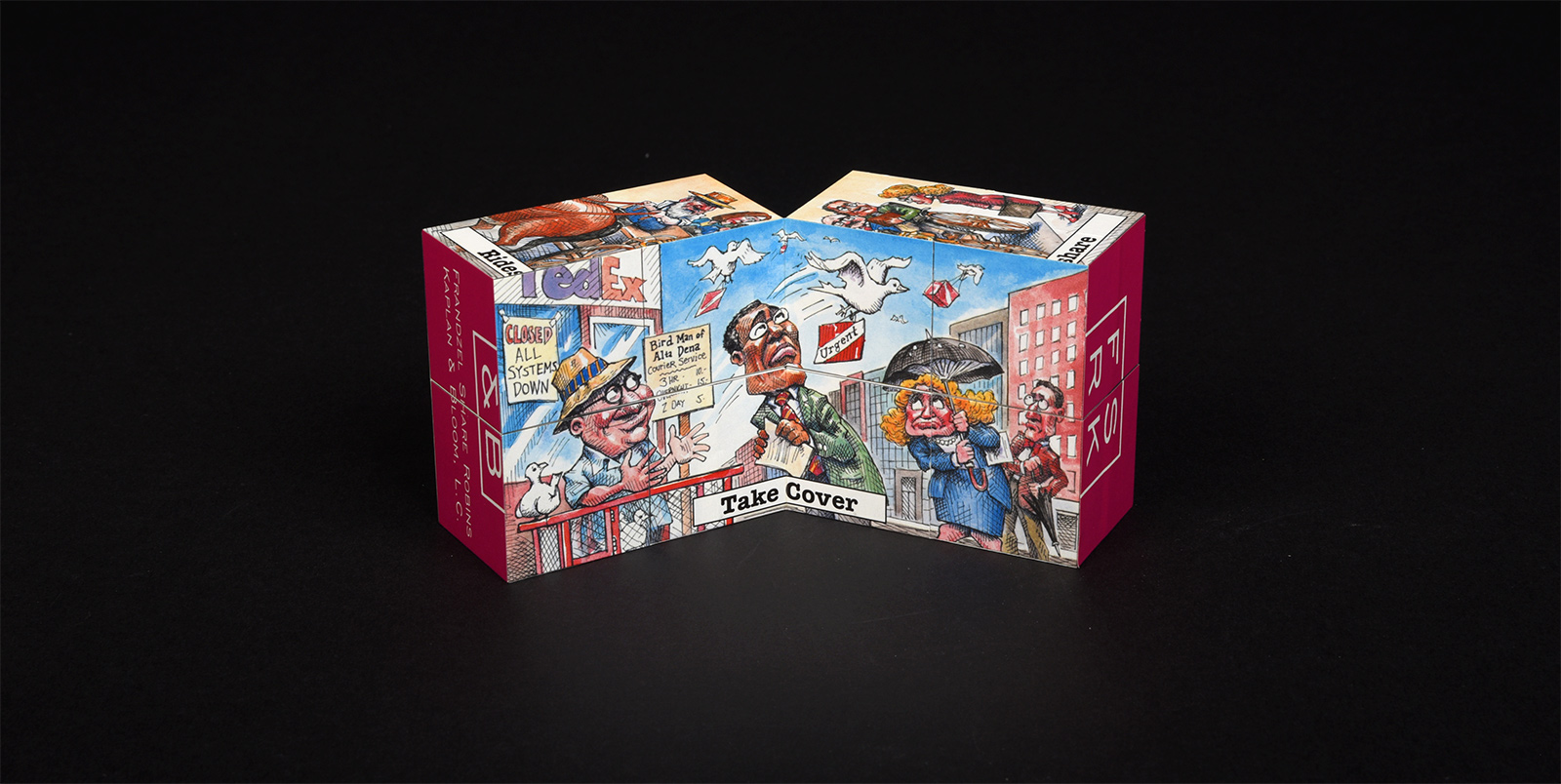

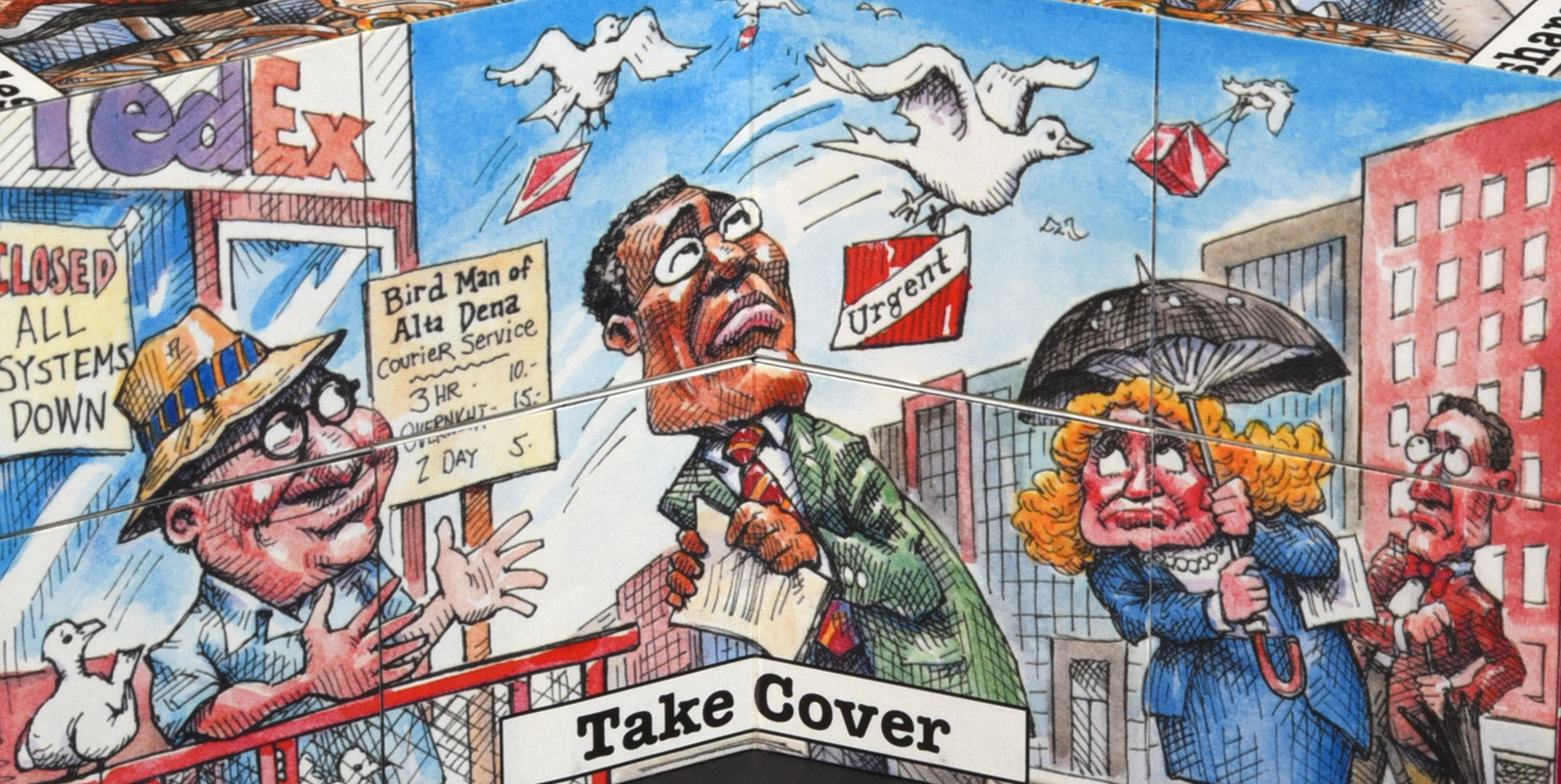

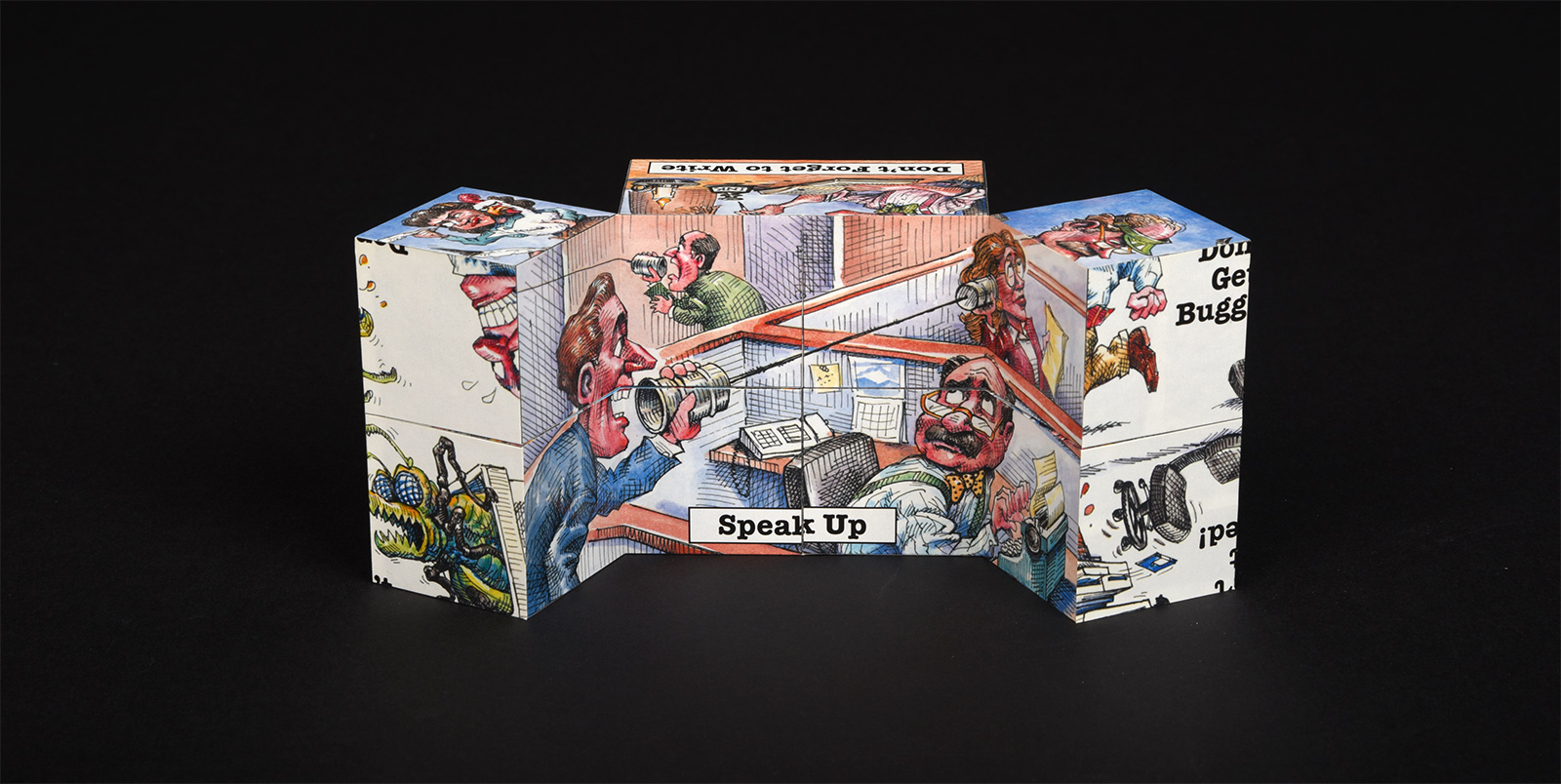

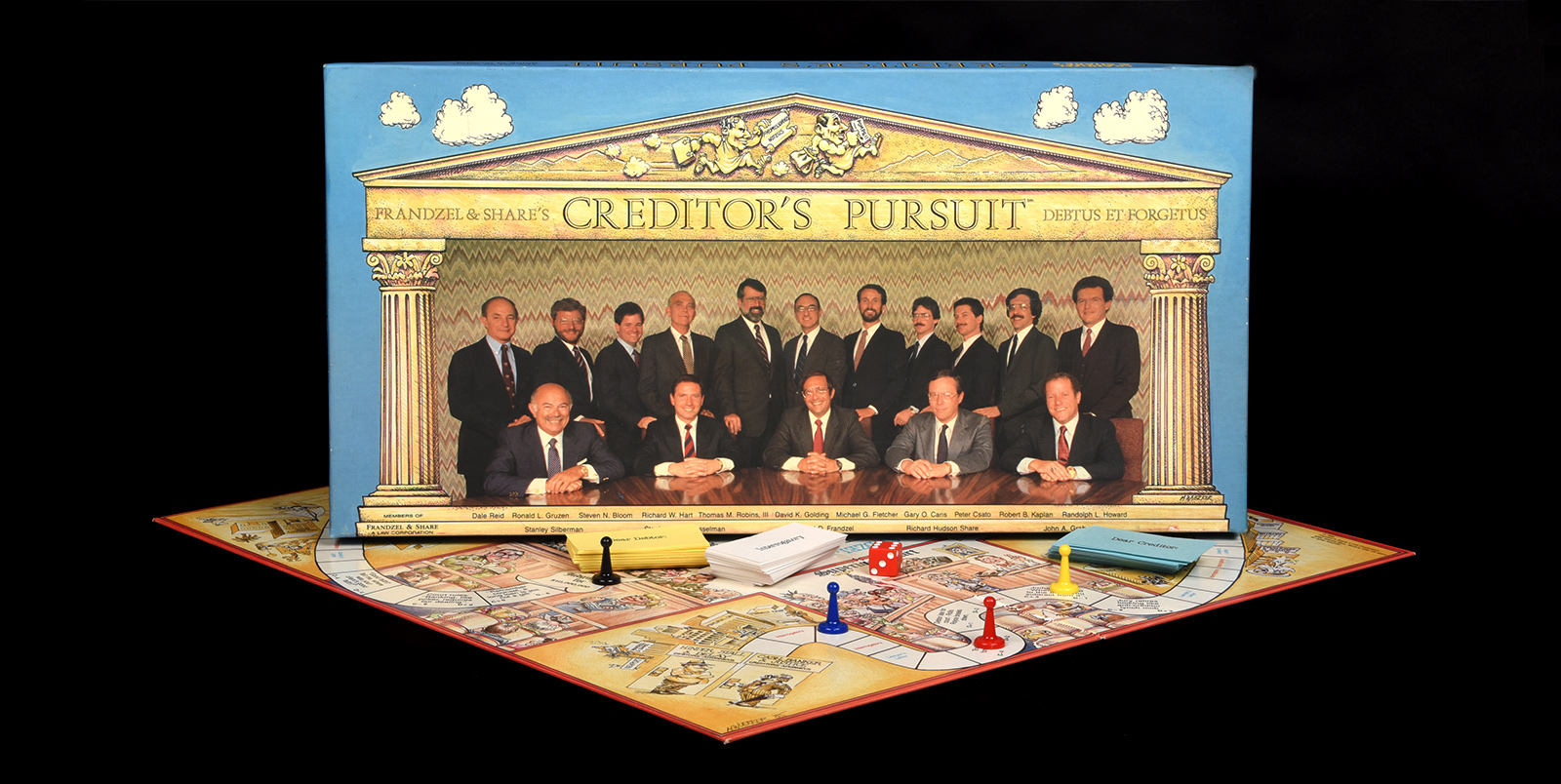

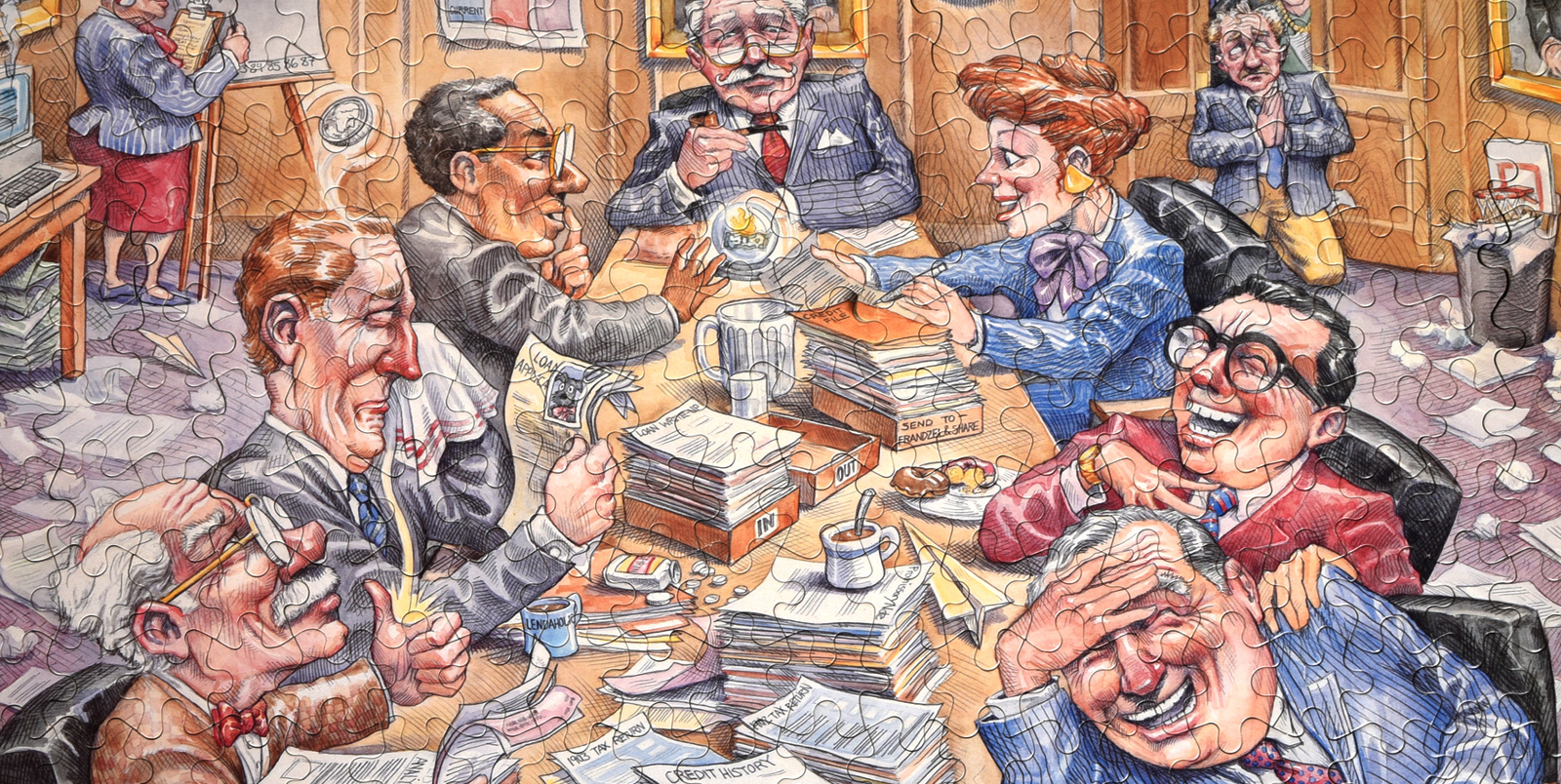

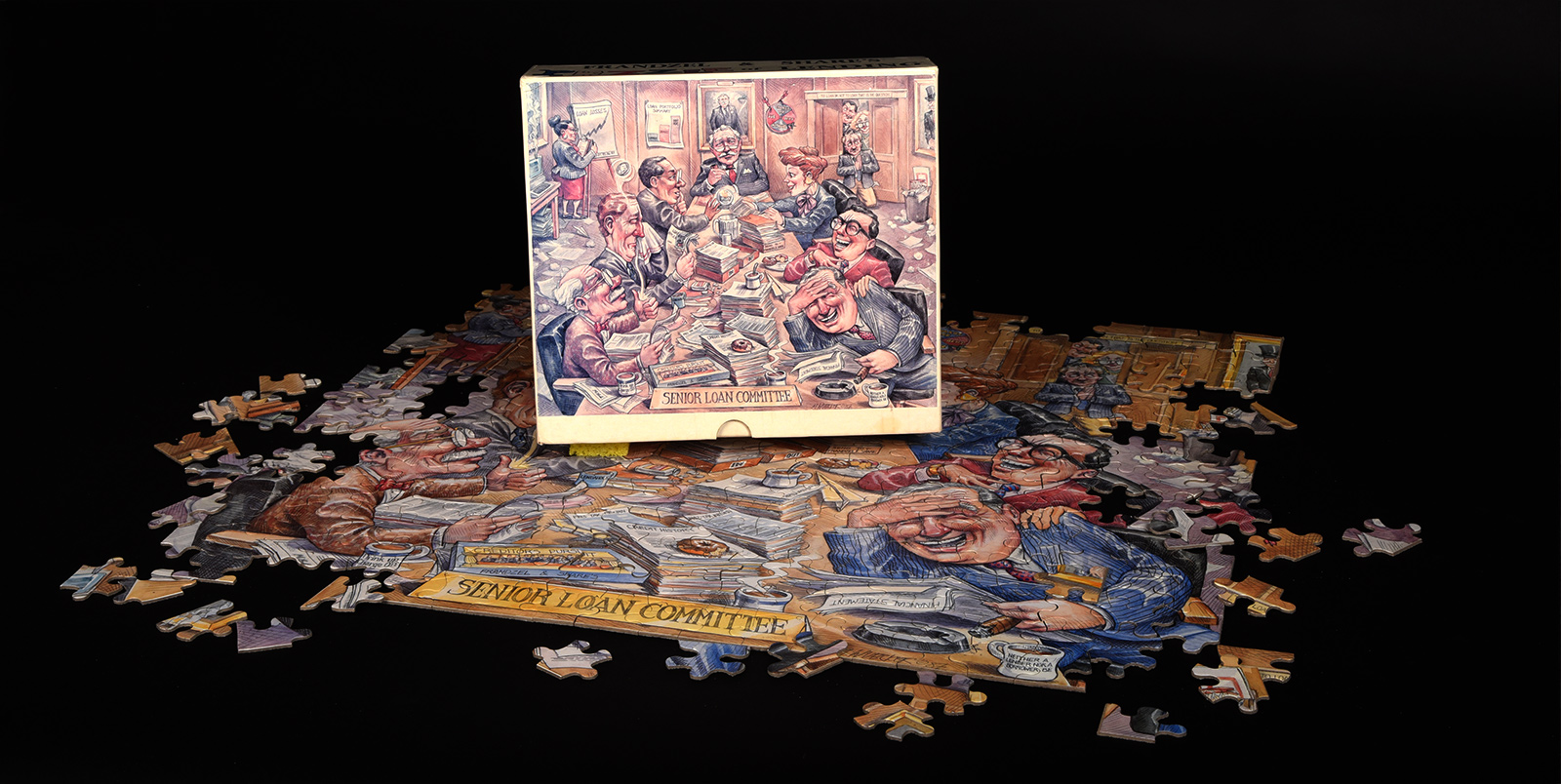

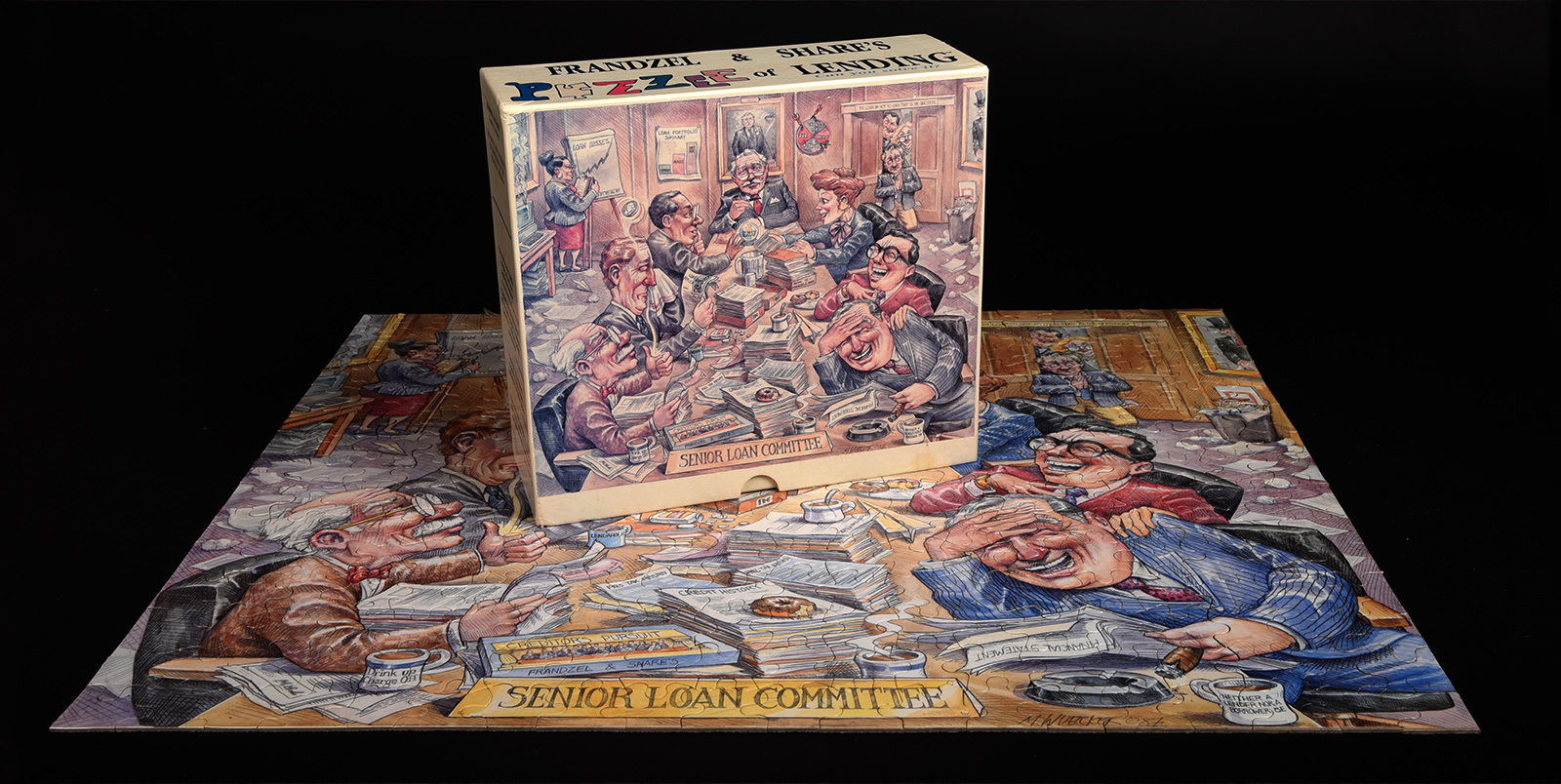

In 1979, Bob Frandzel founded what is today known as Frandzel Robins Bloom & Csato, L.C. Bob, with his unbound energy and enthusiasm, envisioned a state of the art go-to creditors’ rights and commercial law firm, and set out to create it with lawyers that shared his vision – but didn’t take themselves too seriously (as exemplified by the games, such as “Creditors’ Pursuit”, “Daze of our Loans” and “The Creditors’ Deal” that we created for our clients and friends over the years).

The games we created some years ago are a wonderful reminder of our caring culture and ability to laugh and have fun. But our philosophy was and is simple: every client is important, and we will do what it takes to get the job done. Whether closing a deal, litigating a dispute, or providing counsel, the success of our clients is our measuring stick.

The Commercial Real Estate Finance Council (“CREFC”), the trade association for the $3.9 trillion commercial real estate finance industry, started 2018 off with a bang in setting an attendance record of over 1,800 people at its annual conference on January 8-10 in Miami.

Optimism among the attendees was extremely high, as demonstrated by many of the comments made during the various panel presentations. One panel that caught my attention was a discussion concerning where we are in the real estate cycle. While many acknowledge that we “should be” approaching what would generally be the end of a ten-year real estate cycle, there is a lot of support for the view that there is no end in sight for the current cycle, and that it might actually go on for another five-plus years, unless some extracurricular event takes place that could throw the cycle out of whack. Most people base their view of an extended cycle on the fact that interest rates remain at historically low rates and that there is incredible liquidity in the marketplace. From an intrinsic standpoint, two factors which could prevent the “extension” of the cycle are interest rates rising faster than expected and regulatory volatility.

There were two other issues that were discussed that I thought were of particular interest. First, there was general consensus that borrowers are putting much more equity into deals than they did in prior cycles, with many deals having at least 40% equity in them at the outset, as borrowers/investors have learned that the higher leveraged deals were much more difficult to save in the last downturn. Additionally, alternative lenders are putting substantial pressure on traditional lenders due to the lack of regulatory constraints, while community banks are once again becoming a real force in what appears to be a very aggressive, competitive financing marketplace.

All in all, the mood at the first major real estate conference of the year was of high energy, enthusiasm and optimism – I guess we shall see how this all turns out!

CRE Finance Council (“CREFC”) started 2018 off with a bang in setting an attendance record of over 1,800 people at its annual conference on January 8-10 in Miami.

Optimism among the attendees was extremely high, as demonstrated by many of the comments made during the various panel presentations. One panel that caught my attention was a discussion concerning where we are in the real estate cycle. While many acknowledge that we “should be” approaching what would generally be the end of a ten-year real estate cycle, there is a lot of support for the view that there is no end in sight for the current cycle, and that it might actually go on for another five-plus years, unless some extracurricular event takes place that could throw the cycle out of whack. Most people base their view of an extended cycle on the fact that interest rates remain at historically low rates and that there is incredible liquidity in the marketplace. From an intrinsic standpoint, two factors which could prevent the “extension” of the cycle are interest rates rising faster than expected and regulatory volatility.

There were two other issues that were discussed that I thought were of particular interest. First, there was general consensus that borrowers are putting much more equity into deals than they did in prior cycles, with many deals having at least 40% equity in them at the outset, as borrowers/investors have learned that the higher leveraged deals were much more difficult to save in the last downturn. Additionally, alternative lenders are putting substantial pressure on traditional lenders due to the lack of regulatory constraints, while community banks are once again becoming a real force in what appears to be a very aggressive, competitive financing marketplace.

All in all, the mood at the first major real estate conference of the year was of high energy, enthusiasm and optimism – I guess we shall see how this all turns out!

There is a big ticket item for asset-based lenders in California, and particularly for lenders holding more than one deed of trust on the same property. On September 27, 2017, the California Supreme Court granted review of Black Sky Capital, LLC v. Cobb (2017) 12 Cal.App.5th 887 (“Black Sky“) and is now poised to answer the following question:

Does Code of Civil Procedure section 580d permit a creditor that holds both a senior lien and a junior lien on the same parcel of real property arising from separate loans to seek a money judgment on the junior lien after the creditor foreclosed on the senior lien and purchased the property at a nonjudicial foreclosure sale?

For decades now, California courts have answered this question in the negative, citing the equitable rule created in the case of Simon v. Superior Court (1992) 4 Cal.App.4th 63 (“Simon“). The Simon rule provided creditors with a bright-line prohibition: if the lender holds separate notes secured by senior and junior deeds of trust, then the lender is barred from collecting anything on the “sold-out” junior debt after it nonjudicially forecloses on its senior deed of trust. By contrast, where the senior and junior lenders are different entities, the “sold-out junior” whose lien is extinguished by the unrelated senior’s foreclosure may freely sue the borrower on its (now unsecured) loan, obtain a money judgment, and collect its debt by execution on the borrower’s other assets.

The Simon rule is based upon a perceived need to prevent lenders from opting-out of California’s antideficiency scheme, and in particular Code of Civil Procedure section 580d, which prevents a lender from collecting a deficiency after nonjudicial foreclosure of the deed of trust securing the debt. The Simon court reasoned that the purpose (if not the text) of section 580d would be subverted if a lender could simply structure one loan into two loans secured by separate trust deeds. Notably, the Simon rule is quite broad, applying to situations regardless of the lender’s actual motives in structuring the original loan. In other words, under Simon‘s rule, the lender’s intent (to evade antideficiency legislation or not) is simply not relevant and, under Simon, even a lender with demonstrably legitimate reasons for structuring a loan with two separate notes and two trust deeds would be barred from collecting its sold-out junior debt. This is concerning, since so-called “piggyback” refinancing transactions, where junior and senior liens are created at the same time, are rather common.

In June of 2017, the California Court of Appeal published Black Sky, a case which rejected Simon‘s holding and found that nothing in section 580d prevents any sold-out junior from collecting its debt. In Black Sky, a bank loaned about $10 million to two individual borrowers secured by a deed of trust on a parcel of commercial real property. Two years later, the same bank loaned another $1.5 million to the same borrower, secured by a second deed of trust on the same property. The bank later assigned both the notes and deeds of trust to Black Sky. The borrowers defaulted, and Black Sky nonjudicially foreclosed on the senior lien and acquired the property for a $7.5 million credit bid. Black Sky then sued the borrowers for on the sold-out junior debt. The trial court granted summary judgment in favor of the borrowers—citing Simon‘s rule: that section 580d prevents a lender from collecting its sold-out junior debt after the same lender forecloses on its senior deed of trust. Black Sky appealed.

On appeal, the Court of Appeal reversed the trial court, finding that section 580d did not apply. (Black Sky Capital, LLC v. Cobb (2017) 12 Cal.App.5th 887, 897 [“By using the singular throughout the statute, the Legislature unambiguously indicated that section 580d applies to a single deed of trust; it does not apply to multiple deeds of trust, even if they are secured by the same property… It makes no difference whether the junior lienholder is the same entity or a different entity as the senior lienholder.”].)

Assuming the California Supreme Court addresses the Simon vs. Black Sky interpretations of section 580d head-on, lenders will finally be provided with certainty on what has, to date, been a murky landscape for lenders trying to protect themselves in strategically structuring financing transactions. We will be monitoring the progress of the Black Sky appeal as it progresses in the California Supreme Court, and will provide an immediate update once a substantive decision is rendered.

While Bitcoin may be a bubble or passing fad, the technology behind it will revolutionize the way we do business in the near future

Part I: What is Blockchain?

While Bitcoin became a household name in 2017, most people know little of the technology underpinning the digital currency. This technology, known as “blockchain,” has far reaching implications beyond digital currency, and will likely revolutionize the way we do business in the near future. In a 2017 study conducted by Gartner, Inc., it estimates that the business value-add of blockchain will grow to slightly more than $176 billion by 2025, and will likely exceed $3.1 trillion by 2030. In fact, a World Economic Forum report from September 2015 predicts that by 2025, ten percent of global GDP will be stored on blockchain technology.

In a January, 2017 Harvard Business Review Article titled “The Truth About Blockchain,” professors Marco Iansiti and Karim R. Lakhani describe blockchain as a foundational technology that may not immediately overtake our traditional business models, but has the potential to create new economic and social systems and enormously change the way we transact over the coming decades. Moreover, companies already see the writing on the wall – IBM, Microsoft and Intel are offering blockchain software tools to their business customers, Goldman Sachs, Nasdaq, Walmart, Visa and the State of Delaware all have started blockchain initiatives.

How could such a new and little known technology have such massive business implications? In this series of articles, we will first provide a general overview of what blockchain technology is and how it works. In our second piece, we will provide an overview of how blockchain will change a variety of industries. Finally, in our third piece, we will provide a more in-depth look at how blockchain will impact the legal industry, contracts and financial institutions.

While Bitcoin uses a specific implementation of the blockchain, blockchain in general can be described as a decentralized, shared, public ledger that is maintained by a network of computers that verify and record transactions into the same decentralized, shared, and public ledger. No single user controls the ledger – it is maintained by all of its participates, in the cloud, or by a network of designated computers that collectively keep the ledger up to date and verify its transactions. Bitcoin, as the largest implementation of blockchain technology today, uses competitive “miners,” or individual users that solve ever more difficult math equations with monetary rewards if they are successful, to verify and record transactions.

When a transaction is verified and recorded, the blockchain system sends transaction data to all of the users of the blockchain ledger, thereby ensuring the validity and accuracy of the transaction and prevents one party to the transaction from lying about the details or failing to perform. Each transaction, or “block,” is encrypted into its own original piece of information, which is called a “hash.” Even the slightest modification of data will result in an entirely different hash. For example, in applying SHA256, the encryption algorithm used by Bitcoin, to the number 1000 generates the following hash, “40510175845988F13F6162ED8526F0B09F73384467FA855E1E79B44A56562A58” while the hash for the number “1000.01” generates a wildly different result in “6B481FC35196FA215BB30D39ECB919CE7DE410488EC08D692356E22E5A67B2B9.” Because each hash is unique, it becomes exceptionally difficult to tamper with the system as it is nearly impossible to generate an identical hash to fool the system.

Essentially, blockchain is a tool where trustworthy records of transactions can be kept, verified, and made publicly available. Blockchain is revolutionary because it creates confidence between counterparties and negates the need for neutral third-parties or transactional facilitators, such as escrow companies, government authorities or clearing houses. Transactions are “peer-to-peer,” or directly contracting party to contracting party. If there’s a disagreement, there’s no need to call a lawyer because there is only one database.

The implications of blockchain will be enormous and will impact almost every industry. 2018 is likely to be a huge turning point for blockchain technology and the year we see the technology significantly implemented beyond Bitcoin. As we will discuss in Part II of this article, there are a wide variety of businesses and industries that are currently experimenting with blockchain technology.